|

|

Chorale Melodies used in Bach's Vocal Works

Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein |

|

Melody & Text | Use of the CM by Bach | Use of the CM by other composers |

| |

|

Melody & Text: |

|

Most representative of the daily prayers are the two closely associated chorales related to the theme of “Death and Dying,” with their similar text form: "Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein" (When we are in utmost need) and “Vor/Für deinen Thron tret ich hiermit” (Before thy throne I now appear). "Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein" in seven stanzas was created in the mid-16th century Reformation and is found in the NLGB as No. 277, "Cross, Persecution and Tribulation.” “Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit” (Fischer-Tümpel II: 409-10, EKG 486) was written a century later in 15 stanzas involving Trinitarian addresses, thanksgiving and eternal life. Although not found in the NLGB, it was a representative devotional hymn in J.S. Bach’s time. It is widely known as J.S. Bach’s so-called “death-bed chorale,” which began as the brief Weimar Orgelbüchlein chorale prelude (Ob. 100), "Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein," BWV 641 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPMeBNU9fes). This was expanded to a “Leipzig” chorale prelude, BWV 668(a), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52RdshARXdg).

J.S. Bach renamed and altered it as “Vor deinen Thron,” the last music in his Art of the Fugue, published posthumously (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DcXvkVAxc-Q) In other hymnbooks such as Freylinghausen’s Geist-reiches Gesangbuch (Halle, 1708), the text of "Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein” also was associated with other melodies besides Martin Luther’s in its original use, while the succeeding chorale, “Vor deinen Thron,” also had other melodic associations. In both chorales the identified melody also had other, subsequent textual associations, as was the practice increasingly in chorale history from the Reformation onward. Debates still continue among J.S. Bach scholars as to which setting was composed first, BWV 668 or 668a (sometimes used interchangeably and with either text incipit), although the former is a revision and exists in an incomplete manuscript (anonymous copyist) of 25 1/2 bars. Each has a different incipit and are variant settings.

Which stanza did J.S. Bach emphasize most in his musical treatment?, asks Leahy, whose book examines all 18 chorale preludes from this perspective. “As Bach drew close to the end of his life, he would choose to depict the deeply personal and eschatologically strong Stanza 1 in the final composition in this collection,” she says (Ibid.: 278). “In effect the sinner is asking for salvation and forgiveness of sin, as in stanza 6 of "Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein".

"Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein,” BWV 668, is a plea of forgiveness in the seven-stanza text of Paul Eber (1564), based on Jehoshaphat's prayer in 2 Chronicles 20, set to the Louis Bourgeois 1543 melody (Zahn 394, BCW melody information, http://www.bach-cantatas.com/CM/Herr-Gott-loben-alle.htm. J.S. Bach set the Louis Bourgeois melody in the plain chorales, BWV 431 in F Major and BWV 432 in G Major, as well as in the organ chorale preludes of the Weimar Orgelbüchlein collection, BWV 641 in F Major, under the heading "Christian Life and Conduct." It is possible that the two plain chorales and the organ chorale prelude (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKL-wLGhoAU), were performed during Leipzig services on the 16th Sunday after Trinity, where the four Cantatas for that day, BWV 161, BWV 95, BWV 8, and BWV 27, were performed.

Source: Devotional Hymns: Morning, Evening Songs (December 14, 2017) |

|

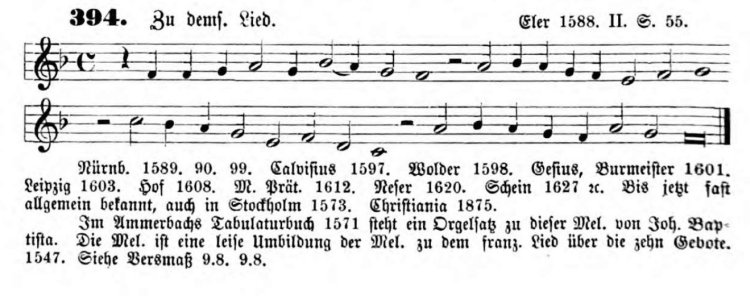

Melody: Zahn 394

Composer: Anon (1588), after the melody Melody “Leve le cœur” by Louis Bourgeois (1547) |

|

|

|

|

Melody: “Leve le cœur” by Louis Bourgeois (1547) |

Melody: “Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein” (1588) |

|

The melody (supra) is by Louis Bourgeois. It appeared first in the French Psalter of 1547: Pseaulmes cinquante de David, Roy et prophete, traduictz en uers francois par Clement Marot et mis en musique par Loys Bourgeoys, à quatre parties (Lyons, 1547). It is set there to the hymn on the Ten Commandments, “Leve le cœur, ouvre l’oreille.” The tune was attached to Paul Eber’s hymn by Franz Eler, in his Cantica sacra (Hamburg, 1588). There are harmonizations of the melody in Choralgesänge, Nos. 358, 359 (BWV 431, BWV 432). The tune does not occur in J.S. Bach elsewhere than in the Organ works infra (BWV 641, BWV 668). His text is invariable. Witt’s (No. 656) is uniform with it. |

|

|

Text: Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein (NLGB 277; EG 366; Gemeindelieder 57; Jesus unsere Freude! 490; ELG 546)

Author: Paul Eber (1566), after In tenebris nostrae by Joachim Camerarius (c1546) |

| |

| |

|

Use of the Chorale Melody by Bach: |

|

Text: Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein |

|

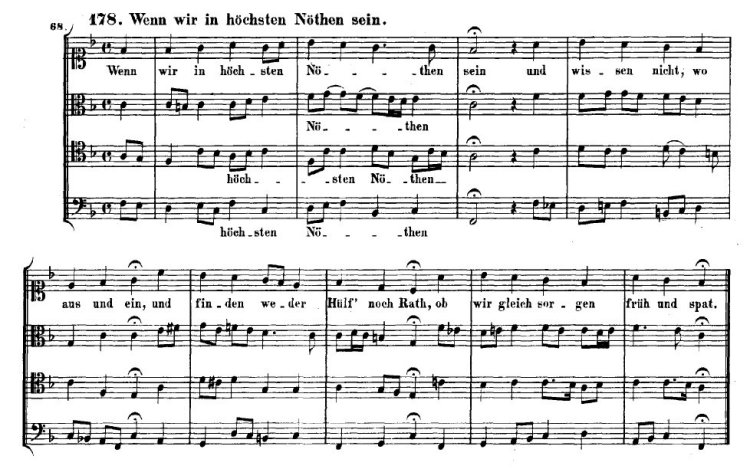

Chorale Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein, BWV 431

Ref: RE 68; Br 68; KE 358; Birnstiel 72; Levy-Mendelssohn 54; Fasch p.85; BGA

178; BC F203.1 |

|

|

Chorale Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein, BWV 432

Ref: RE 247; Br 247; KE 359; AmB 46II p.67; BGA 179; BC F203.2 |

|

|

Untexted: |

|

Chorale Prelude Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein, BWV 641 |

|

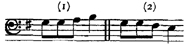

A short movement of nine bars in the “In Time of Trouble” section of the Orgelbuchlein. It will be noticed that J.S. Bach constantly states and inverts the opening four notes of the cantus, |

|

|

|

The effect, as Schweitzer notes, is that the three lower parts constantly voice the urgency of their “utmost need,” while over their lament the melody flows along “like a divine song of consolation, and in a wonderful final cadence seems to silence and compose the other parts.” The cantus itself is treated in J.S. Bach’s most intimate and reflective manner, as though he sought to convey through its short phrases the utmost of the intense feeling that filled his own soul. |

| |

|

Chorale Prelude Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit (I), BWV 668 |

|

Chorale Prelude Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit (II), BWV 668a |

|

The movement is the last of the Eighteen Chorals. During J.S. Bach’s last illness he continued to revise his Organ Preludes, a work upon which he had been engaged for some time. He was almost blind and passed his days in a darkened room. Paul Eber’s hymn had brought comfort to many in their distress, and to its melody J.S. Bach turned in the last weeks of his life. His strength no longer being equal to the effort, he dictated to Johann Christoph Altnikol, his son-in-law, this movement a melody he had treated years before in the Orgelbuchlein. “In the dark chamber,” writes Schweitzer finely, “with the shades of death already falling round him, the master made this work, that is unique even among his creations. The contrapuntal art that it reveals is so perfect that no description can give any idea of it. Each segment of the melody is treated in a fugue, in which the inversion of the subject figures each time as the counter-subject. Moreover, the flow of the parts is so easy that after the second line we are no longer conscious of the art, but are wholly enthralled by the spirit that finds voice in these G major harmonies. The tumult of the world no longer penetrated through the curtained windows. The harmonies of the spheres were already echoing round the dying master. So there is no sorrow in the music; the tranquil quavers move along on the other side of all human passion; over the whole thing gleams the word ‘Transfiguration.’ ”

But it was not Paul Eber’s hymn that J.S. Bach employed to disclose the spirit of his music. His was no cry of distress, but the simple faith of a devout nature facing eternity, and ready to meet it, with the words of a prayer of daily use upon his lips. J.S. Bach bade J.C. Altnikol inscribe the music with the title “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiemit.” The hymn was first published by Justus Gesenius and David Denicke in the New Ordentlich Gesang-Buch (Hannover, 1646), and is entitled “Am Morgen, Mittag und Abend kan man singen” (For use morning, mid-day, and evening). Its authorship is attributed, on certain grounds, to Bodo von Hodenberg, who was born at Celle in 1604 and died in 1650 at Osterode, where he then was Landrost. The Novello Edition (xv. 114; xvii. 185) quotes B.v. Hodenberg’s (?) hymn as “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich allhier.” Fischer-Tümpel (ii. 410) does not sanction this form. The hymn had its proper melody (Zahn, No. 669) since 1695, but neither hymn nor melody was in general use: the former is not in the Unverfälschter Liedersegen (Berlin, 1851).

“Death,” writes Sir Hubert Parry1, “had always had a strange fascination for J.S. Bach, and many of his most beautiful compositions had been inspired by the thoughts which it suggested. And now he met it, not with repinings or fear of the unknown, but with the expression of exquisite peace and trust. Music had been his life. Music had been his one means of expressing himself, and in the musical form which had been most congenial to him he bids his farewell; and only in the last bar of all for a moment a touch of sadness is felt, where he seems to look round upon those dear to him and to cast upon them the tender gaze of sorrowing love.”

The foundation of the movement is the Orgelbuchlein Prelude (supra), minus its elaborate ornamentation of the cantus, and with the addition of the astonishing interludes on which Schweitzer’s commentary already has been quoted. |

| |

| |

| |

|

Use of the Chorale Melody by other composers: |

| |

| |

|

Sources: Bach Digital; BGA; Zahn

Prepared by Aryeh Oron (October 2018) |

|

|