|

|

Andreas Hammerschmidt (Composer, Hymn-Writer) |

|

Born: December 1611 - Brüx [now Most], Bohemia, Germany

Died: October 29, 1675 - Zittau, Germany |

|

Andreas Hammerschmidt [Hammerschmid, Hammerschmied], was a German composer and organist of Bohemian birth. He is the most representative composer of mid-17th-century German church music, of which he was a prolific and extremely popular exponent. |

|

Life |

|

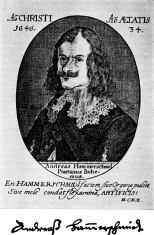

It is impossible to establish Hammerschmidt’s exact date of birth since the church registers of the independent Protestant community at Brüx (which lasted only from 1609 to 1622) have been lost; the available information derives from his tombstone and from portraits of him. His father, Hans Hammerschmidt (b Carthause, nr Zwickau, 1581; d Freiberg, Saxony, 1636), was of Saxon descent and was a saddler in Bohemia, first at Saaz and from 1610 at Brüx, and his mother probably came from Bohemia; they were married by 1609. Because Bohemia again became Catholic during the Thirty Years War, the Hammerschmidt family had to leave Brüx in 1626. In 1629 Hans Hammerschmidt became a freeman of Freiberg, Saxony. Nothing is known about Andreas Hammerschmidt’s early education: by this date there was no Gymnasium at Brüx, and his name does not appear in the registers of the Gymnasium at Freiberg. Johann Christoph Demantius, Kantor and leading musical personality at Freiberg from 1604 to 1643, was probably not his actual teacher (though they probably knew each other), and he may have served some kind of apprenticeship with one of the other Freiberg musicians. No connection with the organist Balthasar Springer is known, and the assumption that he was taught by Christoph Schreiber is based solely on the fact that he later succeeded Schreiber in two of his posts. For many years it was thought that Andreas Hammerschmidt received his early musical training from the Kantor Stephan Otto at Schandau in Saxony. Recent reseaches have reveales that it is unlikely that he was a pupil of Otto, since Otto returned to Freiberg only in 1631, but there was a long-lasting friendship between them, as Hammerschmidt’s commendatory poem in Otto’s Kronen-Krönlein (1648) indicates. From July 1633 to 1634 Hammerschmidt was organist in the service of Count Rudolf von Bünau at the castle at Weesenstein, Saxony, where Otto was Kantor. After Schreiber’s departure for Zittau, he applied on October 9, 1634 for the post of organist at the Petrikirche, Freiberg, and was elected on December 8. He may have taken up his duties in the New Year, though he was formally appointed only in July 1635. The Petrikirche was the leading organist’s post at Freiberg, though the salary was barely a living wage. Hammerschmidt’s first printed work, Erster Fleiss, dedicated to the mayor and councillors of Freiberg, appeared there in 1636. He may well have composed the first part of the Musicalische Andachten (1639) for use in services at the Petrikirche. On August 22, 1637 he married there Ursula Teuffel, the daughter of a Prague businessman; of their six children, three died in infancy.

After Christoph Schreiber’s death Hammerschmidt was appointed his successor as organist of the Johanniskirche, Zittau; on November 18, 1639 he parted from the Freiberg council with a letter of thanks; this was to be the last and most important position of his career. It was at Zittau that he produced the greater part of his music and became genuinely popular (the ‘world-celebrated Herr Hammerschmied’, Johann Rist called him in 1655). An appointment to Denmark, alluded to in M.T. Petermann’s laudatory poem in the Ander Theil geistlicher Gespräche über die Evangelia (1656), cannot be confirmed. Nothing is known of his applying for any other position or of his being away from Zittau except on journeys to such places as Bautzen, Dresden, Freiberg, Görlitz and Leipzig. (Archival records at Zittau covering his 36 years there were destroyed by fire in 1757.) Until 1662 he was the only organist at Zittau. The Johanniskirche, the principal church there, contained three organs opposite each other and thus provided ideal possibilities for the realization of the concerted style. Throughout Hammerschmidt’s stay at Zittau the Kantor at the Johanniskirche and at the Johanneum (the local Gymnasium) was Simon Crusius. The early work of both men coincides with the Thirty Years War, during which the school and the choir were decimated. Conditions slowly improved after the war, but it was only after they were dead that musical life really began to flourish again. Nevertheless, during their partnership the position of organist became one of real importance. The organist was required to compose and perform vocal music to the organ. He directed the soloists from the school choir and the instrumental ensemble from the town musicians, while the Kantor was responsible for the choral liturgical music. Hammerschmidt consequently became a very prolific composer. The many laudatory poems prefacing his publications, among them verses by such prominent men as Schütz and Johann Rist, bear witness to the high esteem in which he was held. He also had a large number of pupils and was the only person in Zittau entitled to give keyboard tuition. He was often called upon as an organ expert (for example at Bautzen in 1642 and at Freiberg in 1659 and 1672). The Zittau council appointed him village and forest superintendent for Waltersdorf an der Lauscha. All these activities enabled him to live in considerable affluence. In 1656 he bought a house in Webergasse, directly opposite the Johanniskirche, and added to it by the purchase of a garden; in 1659 he bought a plot of land outside the town and built a summerhouse on it His dedications and prefaces and his personal correspondence reveal a notably cultured and educated man. Christian Keymann [Keimann], vice-Rektor (1634) and Rektor (from 1638) of the Johanneum, whose poems he set to music, and Theophil Lehmann, the leading ecclesiastic, were among his closest friends; Keimann was almost certainly to blame for the later souring of their relationship. The two surviving portraits of him, in the fourth part of the Musicalische Andachten (1646) and in the Missae (1663; see illustration), reveal individual and passionate features, probably not incompatible with sudden outbursts of rage. The stories of fights with Johann Rosenmüller at Leipzig and with an innkeeper at Zittau are not well documented. In his last publication, in 1671, he wrote of his ‘now wearisome life’ and expressed the wish that his ‘diligence shown up to now might be concluded’; he was apparently already suffering from senile decay. He died on October 29, 1675; his funeral (3 November) was well attended; and his tombstone describes him as the ‘Orpheus of Zittau’. |

|

Works |

|

Andreas Hammerschmidt was one of the most distinguished composers of church music in the 17th century; he contributed prolifically to the choir and congregational music of his day. Most of Hammerschmidt’s output consists of sacred vocal works: he published more than 400 of them in 14 collections, all more or less adhering to the concertato principle. According to his own classification they comprise works in the forms of the motet, concerto and aria. He himself said that in his motets he felt bound by tradition, whereas he saw the concerto as a truly up-todate form. He did not always escape the dangers of mechanical, stereotyped writing. His arias, however, in their melodic lines, treatment of text and formal plan, prefigure subsequent developments in the German cantata. The second and fifth parts (1641, 1652-1653) of the Musicalische Andachten include motets that are madrigalian in their emphasis on the text. The second part contains 34 ‘sacred madrigals’ to German words for four to six voices; 12 pieces for five voices and four for six may be reinforced here and there by a small chorus (‘Capella’). The fifth part, containing 29 German and two Latin works for five and six voices, also contains ‘choral music in the madrigal style’. In his preface Hammerschmidt indicated the similarity of this music to Schütz’s Geistliche Chor-Musik (1648) and added a commendatory poem by Schütz. He returned to this motet style in his last collection, the six-part Fest- und Zeit-Andachten (1671), which contains 38 German works. Whereas previously the emphasis had been on the exposition of the imagery and affective elements in the text, these late pieces are in a clearer, more polished style alternating between imitative and homophonic sections. The fourth part of the Musicalische Andachten (1646) contains 40 pieces, four with Latin and 36 with German words; they are described as ‘sacred motets and concertos’ and are for five to 12 voices. 21 of them are recognizably motets; those for fewer than eight voices can also be sung without continuo, and the two choirs can combine to sing those for eight voices. Twelve works are concertos with definite solo parts, and the remaining seven are in transitional forms. The concertos scored for a large number of parts include the two sets of Gespräche über die Evangelia (1655-1656), which contain a total of 59 works for Sundays and feast days scored for two to five solo voices and two to five obbligato instruments, usually violins but sometimes flutes, trumpets and trombones. The form of these works anticipates the later development of the German church cantata. The text, usually taken from the Gospels, is presented in the form of a musical conversation; where the biblical text does not provide a conversation, it is extended by the inclusion of meditative or edifying elements or by the insertion of chorale and aria sections so that certain passages begin to assume the character of independent movements. The Kirchen- und Tafel-Music (1662) includes a further 12 concertos for two to five voices with two to five obbligato instruments and also contains ten monodies. This collection makes the most frequent use of chorales, with nine chorale texts altogether.

Sacred concertos for few voices are contained in the first part of the Musicalische Andachten (1639), which consists of 21 pieces for one to four – usually two – solo voices; the words are German biblical or hymn texts. The concertato principle is dominant, and Hammerschmidt only occasionally cultivated true monody. The first book of dialogues (1645) is made up of similar music. Gespräche zwischen Gott und einer gläubigen Seelen (‘Conversations between God and a believer’) is the alternative title of this set of 22 concertos for two to four voices, in which, through ‘dogmatic simultaneous dialogue’ or ‘allegorical didactic dialogue’, as Blume called them, Hammerschmidt achieved a really personal style. The motets for one and two voices (1649) inherited their misleading designation from their Italian models. These 20 works are in fact concertos, 18 with Latin and two with German words, and are Italian in taste, with much more ornamented vocal lines than are usual in Hammerschmidt’s German monodies. In the third part of the Musicalische Andachten (1642), concertos for few voices are enlarged by the addition of instruments; the 31 compositions, with German words, for one and two voices and with two instrumental parts, usually violins, are subtitled Geistliche Symphonien. Finally, the Missae (1663), consisting of 16 Latin missae breves (Kyrie and Gloria, together with a Sanctus in no.15) for five to 12 and more voices, can for the most part be classified as concertos. 12 masses are marked ‘pro organo’ in the original and are concerted works for solo voices and tutti; the remaining four, marked ‘pro choro’, are more motet-like in style. Hammerschmidt ventured into new territory both stylistically and melodically with those works that may be classified as arias. The second set of dialogues (1645) contains 15 song-like arias, 14 for one and two solo voices and two instruments and one for three solo voices; the texts of 12 of them are from Martin Opitz’s paraphrase of the Song of Solomon. The Fest-, Buss- und Danklieder (published at Zittau and Dresden, 1658-1659) is in the same up-to-date song style; its 32 songs to words by poets of the time are mostly scored for five voices with instruments and are in various forms of the aria for several voices.

Although Hammerschmidt was an organist all his life, no organ works by him have survived. His instrumental music is confined to the three collections of pieces that appeared in 1636, 1639 and 1650. With their fashionable dances of the time, continuo part, scoring for viols and their dynamic and tempo markings, the first two collections especially are in the tradition of the English-influenced suites cultivated in north and central Germany, while the third includes free forms such as the canzona, sonata and quodlibet, some of the pieces being scored for the typical brass ensemble (cornetts and trombones) of German town musicians. Finally, mention should be made of Hammerschmidt’s importance as a composer of secular songs through the three parts of his Weltliche Oden (1642, 1643 and 1649). They contain a total of 68 solo songs, duets and trios with violin obbligato that are all settings of poems of the time. In their popular tone, finished workmanship and lyrical feeling they resemble the work of the Hamburg school of songwriters. |

|

|

|

Source: BCL Website [Handbook to the Lutheran Hymnal]; © Oxford University Press 2005 (Author: Johannes Günther Kraner with Steffen Voss); Pictures: MGG1 Bärenreiter, Kassel, 1986 Table 61 MGG1 Vol. 5 & Column 1427 of the same volume

Contributed by Aryeh Oron (August 2003), Thomas Braatz (December 2005) |

|

Texts of Bach Cantatas & Other Vocal Works |

|

BWV 380 |

|

Chorale Melodies used in Bach’s Vocal Works |

|

Freuet euch, ihr Christen alle (1646, EKG: 25, Zahn: 7880a) |

|

Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht (1658, EKG: m Zahn: 3449) |

|

Use of Chorale Melodies in his works |

|

Sonata on Gelobet Seist Du Jesu Christ for alto, 2 trumpets, 4 trombones & continuo (CM: Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ) |

|

Gelobet seist du Jesus Christ , for voice, 2 trumpets, trombones & continuo (from Kirchen- und Tafel-musik) (CM: Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ) |

|

Links to other Sites |

|

Evangelical Lutheran Hymnary Handbook - Biographies and Sources (BCL)

Andreas Hammerschmidt - Biography (AMG) |

|

Bibliography |

| |

|

|